Health

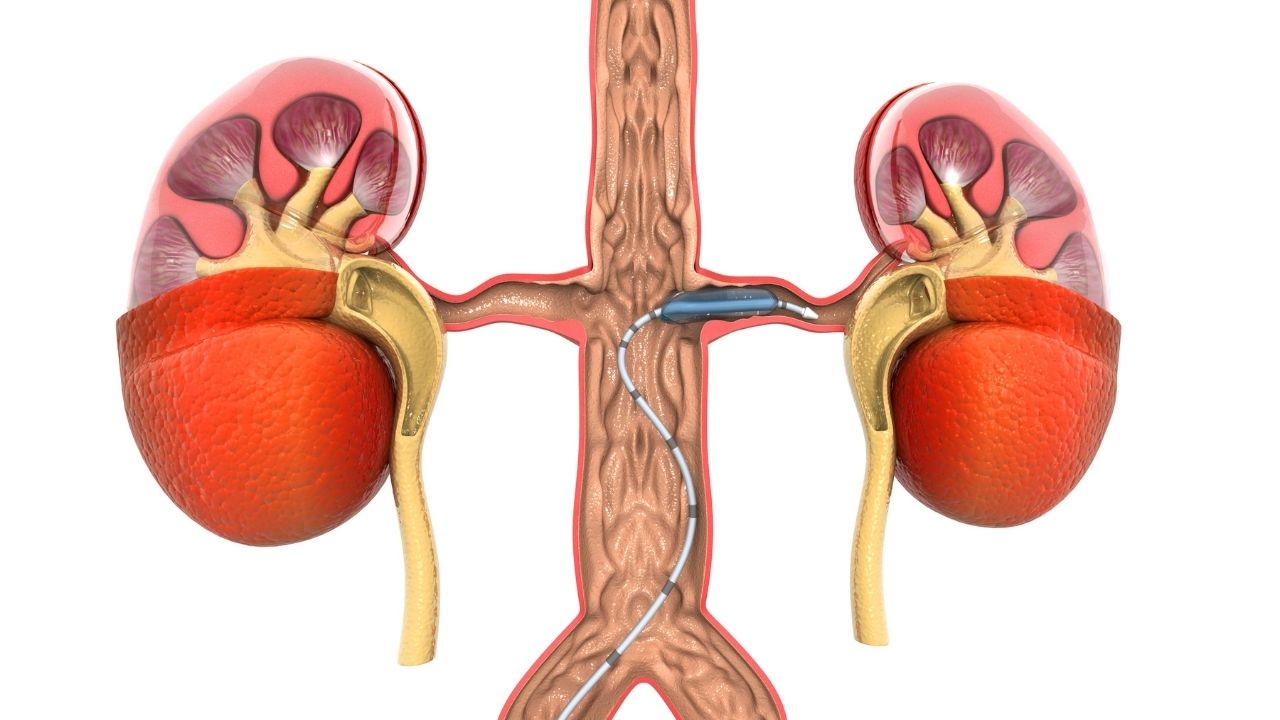

Peripheral Artery Disease

Peripheral artery disease, also known as peripheral arterial disease, is a common circulatory disease that reduces blood flow to the limbs by narrowing arteries. If you suffer from the peripheral arterial disease (PAD), your arms or legs do not receive enough blood to sustain the demand. It mainly affects the legs. You may experience symptoms such as pain while walking. In most cases, peripheral artery disease is usually a sign of fatty deposits in the arteries, a condition known as atherosclerosis. If you live in El Paso and suffer from peripheral arterial disease, you may treat the condition by exercising, eating a healthy diet, and quitting tobacco. If your state does not improve, you may need treatment from a specialist who can diagnose and treat peripheral arterial disease in El Paso.

Symptoms of Peripheral Arterial Disease

Although most people with the disease show no symptoms, you may experience claudication; leg pain while walking. Common signs of claudication include cramping or muscle pain in the legs and arms that come from an activity like walking, but it fades away after resting for a few minutes. The location of the pain varies from one patient to another depending on the narrowed or clogged artery location. Most patients experience calf pain.

The severity of claudication varies from minor discomfort to severe pain. If you experience severe claudication, you may have trouble walking or doing other activities.

Other common symptoms of the peripheral arterial disease include:

- Painful cramping in one or both thighs, hips, or calf muscles after activities such as walking

- Numbness or weakness in your legs

- Coldness in the lower leg or foot

- Sore toes, legs, or feet that do not heal

- Changed skin color affecting your legs

- The slow hair growth or loss of hair on the legs and feet

- The slow growth of toenails

- Shiny skin on the legs

- Weak or no pulse in the legs or feet

- Erectile dysfunction for men

- Pain when using the arms

If the condition advances, it may cause pain even while resting. Sometimes, you may experience severe pain that can disrupt sleep, but you can temporarily relieve the discomfort by moving around or hanging your legs on the edge of the bed.

If you experience numbness, leg pain, or other symptoms, you should see a doctor. You may also need screening if you are older than 65 with a history of smoking and diabetes, or under 50 with diabetes and other risk factors for peripheral arterial disease.

Causes

Atherosclerosis is the primary cause of peripheral arterial disease. Atherosclerosis causes the buildup of fat deposits on your artery walls, reducing blood flow. While it primarily affects the heart, it can also spread to other arteries around your body. The peripheral arterial disease comes about when atherosclerosis spreads to the arteries in your limbs. While it rarely happens, you can also suffer from peripheral artery disease due to inflammation of blood vessels, injuries affecting your limbs, radiation exposure, and unusual anatomy of the limb tissues or ligaments.

In summary, peripheral arterial disease is a circulatory disease that narrows the arteries reducing blood flow to the limbs. While most patients do not show any symptoms, you may have leg pain while walking. It is mainly caused by atherosclerosis.

Health

Choosing the Right Pilates Reformer: A Practical Buyer’s Guide

Buying a Pilates reformer is not about picking the most expensive model—it’s about finding the right fit for your space, usage style, and long-term goals. Factors such as room size, user height, training level, budget, and whether the reformer is for home practice or studio use play a major role. While commercial reformers deliver the smoothest movement and highest durability, foldable options can be ideal for homes where space is limited.

Top Choice for Professional Studio Performance

For those seeking premium, studio-grade quality, the PersonalHour Nano Elite Plus stands out as a leading option. Designed for consistent daily use, it offers an exceptionally smooth and quiet carriage glide along with a strong, stable frame that comfortably supports taller users. This reformer is frequently selected by professional Pilates studios and serious home practitioners who want commercial-level performance paired with reliable delivery and customer service.

Established Names in Commercial Pilates Studios

The Balanced Body Allegro 2 has long been a staple in Pilates studios worldwide. Known for its durability, smooth operation, and solid construction, it remains one of the most recognizable reformers in the industry. Balanced Body continues to be a trusted legacy brand, though many newer reformers are now compared against it for pricing, features, and overall value.

A Balanced Option for Home and Professional Use

The Merrithew SPX Max is often recommended for users who want professional-grade equipment without paying top-tier studio prices. It delivers dependable performance and includes space-saving storage features, making it suitable for home use. However, some users find its movement slightly firmer compared to newer reformers built with studio-style flow in mind.

Best Space-Saving Reformer Without Compromising Quality

When floor space is a concern, the PersonalHour Janet 2.0 is one of the strongest folding reformers available. Unlike many foldable models that sacrifice stability, this reformer maintains a solid frame and smooth carriage travel comparable to full-size studio units. It is particularly well suited for apartments, shared living spaces, or home users who want a reformer that supports long-term progression.

Best Folding Pilates Reformer for Small Spaces

Beginner-Friendly and Budget-Conscious Alternatives

Entry-level and compact reformers, such as AeroPilates models, can be a good starting point for beginners or those practicing occasionally. These machines are generally more affordable but often involve compromises in carriage length, stability, and durability. As a result, they may not be ideal for advanced exercises or long-term use.

What to Look for Before You Buy

Before choosing a Pilates reformer, it’s important to evaluate the following aspects:

-

Carriage performance: Smooth, quiet movement with balanced spring tension

-

Available space: Full-length reformer versus folding or stackable designs

-

User fit: Longer frames provide better comfort for taller users

-

Adjustability: Footbars, jump boards, and accessory compatibility

-

After-sales support: Clear warranty coverage and responsive service

Final Takeaway

If your goal is studio-level performance, the PersonalHour Nano Elite Plus is a standout choice. For homes with limited space, the PersonalHour Janet 2.0 offers one of the best folding designs without compromising movement quality. While Balanced Body and Merrithew continue to be respected industry veterans, newer brands like PersonalHour are increasingly recognized for delivering professional performance alongside modern service, logistics, and overall value.

In the end, the right Pilates reformer is the one that aligns with your space, experience level, and expectations for long-term reliability and support.

-

Tech5 years ago

Tech5 years agoEffuel Reviews (2021) – Effuel ECO OBD2 Saves Fuel, and Reduce Gas Cost? Effuel Customer Reviews

-

Tech6 years ago

Tech6 years agoBosch Power Tools India Launches ‘Cordless Matlab Bosch’ Campaign to Demonstrate the Power of Cordless

-

Lifestyle7 years ago

Lifestyle7 years agoCatholic Cases App brings Church’s Moral Teachings to Androids and iPhones

-

Lifestyle5 years ago

Lifestyle5 years agoEast Side Hype x Billionaire Boys Club. Hottest New Streetwear Releases in Utah.

-

Tech7 years ago

Tech7 years agoCloud Buyers & Investors to Profit in the Future

-

Lifestyle5 years ago

Lifestyle5 years agoThe Midas of Cosmetic Dermatology: Dr. Simon Ourian

-

Health7 years ago

Health7 years agoCBDistillery Review: Is it a scam?

-

Entertainment7 years ago

Entertainment7 years agoAvengers Endgame now Available on 123Movies for Download & Streaming for Free